Emily’s Last Stand

By Dorothy Blanchard

When her classroom emptied, Emily removed the letter from her purse and read it again. Venom rose from the stationary like noxious gas as she read, in part: “... forcing our dear children to adopt the language and customs of that -(Emily cringed) foreigner.” Not surprisingly, the letter was signed, “A concerned Parent.” But Emily recognized the handwriting as that of Florence Bradbury, who was the president of the P.T.A.

When her classroom emptied, Emily removed the letter from her purse and read it again. Venom rose from the stationary like noxious gas as she read, in part: “... forcing our dear children to adopt the language and customs of that -(Emily cringed) foreigner.” Not surprisingly, the letter was signed, “A concerned Parent.” But Emily recognized the handwriting as that of Florence Bradbury, who was the president of the P.T.A.

For a long while she sat staring out across the empty, snow-covered playground. The perfect excuse to skip the Spanish class at Adult Education that night, she thought. And even easier next week. Then drop out completely. Forget about learning Spanish and teaching it to her third-graders. Why make waves, right?

Six months from now, she’d finally retire. She’d had it up to here with whining parents, obstinate school boards, and always having to tap-dance around sensitive areas. Anyway, she thought suddenly, wouldn’t her tiny apartment, with the fireplace glowing, be so ... what was the Spanish word? Simpatico.

Resigned to the decision to drop out of the class, she smartly stacked the papers she had been correcting and let her gaze travel along the empty rows of seats. She stopped at Julio’s. The small, shy, raven-haired boy had slipped quietly as a shadow into her classroom several months earlier. At first the other children had swarmed over him, bombarding him with questions. But disenchanted when he could not answer them, they soon drifted back to their classmates. Julio had sat left alone, deserted, beseeching her with those huge, dark, liquid eyes.

That was when she signed up for the Spanish class. But after the first few weeks, she was ready to quit, thinking it a waste of time. Yet after she had shared what she had learned with her students, the playground chatter rang with “Awesome, amigo,” and “Que pasa, dude?”

When Julio finally joined in the noisy scramble for the candy from a piñata the children had made, she could have shouted for joy. Her newly acquired Spanish skills also enabled her to talk with Julio. She learned that he had been sent to live with his grandmother, who was nearly deaf and unable to respond to the needs of a small boy.

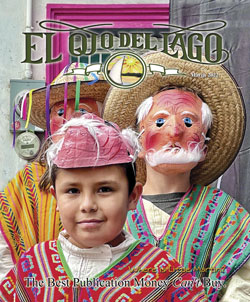

Julio’s entire immediate family had been killed in a beat-up pickup truck, as they were delivering their tomatoes to market. Sensing his need for male guidance, she had found him a Big Brother through United Way. It was all going so well for Julio. But now she had received the “Concerned Parent” letter. It would be followed up, no doubt, by a conference with the school superintendent.

Unexpectedly, she was thrust back to childhood. The first day of school. In her awful black leather high-top shoes and Sunday-best dress so stiffly starched it hurt to move, she had stood propped against a brick wall outside the schoolhouse. She silently practiced all the English words she could remember, as the other children circled her like coyotes. They pointed at her strange European clothes, and giggled and whispered. “Foreigner. She’s a foreigner!”

Mercifully, the bell rang and they all filed inside. Fighting back the stinging tears, she took a seat, and almost jumped out of it when the teacher cracked a rod sharply across a desk. The woman then barked out each child’s name. They rose, one by one, repeated their names and added, “Present.”

Present. Now there was a word Emily knew. What a wonderful school. They were all going to get a present! So, at the sound of her name, she leapt from her seat and called out: “Emily Duschek. PRESENT.”

But when the clock on the wall showed almost two, and no presents had been passed out, Emily began to worry. Perhaps the teacher had forgotten. Emily rehearsed her question several times, then rose and quietly asked: “Will we get our present now?”

The room suddenly went as silent as a tomb. The teacher scowled at Emily like she was a bug crawling across her hand. Emily felt heat rising from her toes all the way to the top of her head, yet couldn’t help finally blurting out: “This morning ... we say ‘present’...so I think--” Then she realized her terrible mistake. The word meant something else. Emily tried to sit down, but her body seemed encased in ice.

As the class slowly caught on, giggles began to float across the room. A red-haired boy with crooked teeth hissed: “Present means you’re here, stu-u-pid!”

In a flash, Emily was across the room, pummeling him with her small fists. The teacher screamed for order, as the rest of the students joined in the melee. Afterwards, Emily was punished.

Yet in the days that followed, she walked a little prouder, held her head a little higher. She couldn’t name what it was she had won, but somehow knew it could never be taken away from her.

Now, staring out at the snow, Emily came out of her reverie. She jammed her orange beret down over her gray curls, pulled on her boots and coat, and raced out toward her car. If she hurried, she could still make that Spanish class.

Some three blocks away, however, she almost ran into the car ahead of her when she glanced over at the Taco Bell restaurant. There, beneath the serape and sombrero sign, sat Florence Bradbury, the president of the P.T.A. The woman who had sent Emily the nasty letter about foreigners was wolfing down a beef burrito grande. A strange giddiness suddenly overtook Emily, as she beeped her horn and sped on.