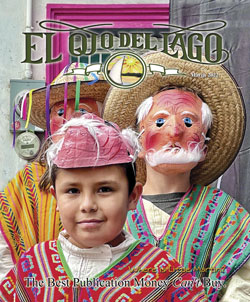

The Old Mexican Man

By Mary Morgan

I approached Real de Catorce from the north, through a tunnel dug over 9000 feet above sea level, its silver mines now silent. Young boys waited eagerly at the other end, competing to lead me through the maze of ancient ribbon-wide streets to “El Centro,” what remained of a Mexican colonial village ghost town.

I approached Real de Catorce from the north, through a tunnel dug over 9000 feet above sea level, its silver mines now silent. Young boys waited eagerly at the other end, competing to lead me through the maze of ancient ribbon-wide streets to “El Centro,” what remained of a Mexican colonial village ghost town.

A small inn, Meson de la Abundancia, was my destination. I parked and turned to press pesos in the chosen child’s palm, then caught a glimpse of the square, its splendor marked for continuing decay. Miguel held the January afternoon sun in his hands as he anchored a corner facing the plaza. Deserted mines, deserted buildings and streets. Deserted minds also? I was keen to discover this remnant of San Luis Potosi’s past.

Descending in time, I climbed stairs to an icy corner room whose stone structure had saved it for the ages. Luggage deposited, I hurried back to the great hall heated by frenzied flames flashing. Warmed and wrapped, I waddled toward the plaza, my duck’s neck extended for a closer glimpse of Miguel.

One of three vendors along the main village street, the only Mexican, his magnetism drew me with a strength conjured from true believers. Catorce is the spiritual center of the earth. Miguel was perched on a plateau above the Huichol’s sacred valley of peyote.

His metal and stone wares lay upon faded fabric. Our introduction and continued awkward signals focused entirely on his work. Semi- crude bracelets, semi-pure metals surrounding semi-precious stones. Multi-faceted, finely carved faces eyed me from different directions. A worn navy pack with webbed trim was crammed with used sacks to pack sales and store his stock each evening.

His hands were gentle, long fingers streaked dark and nails ringed black. Perhaps from carving stone or polishing silver to get the glint of the sunlight they reflected still. (Tiffany’s, I remember, is in New York City.)

Broken bits of language and laughter transacted a sale, prices crudely printed and hardly a word exchanged. Spanish, English, French? The numbers merged. A carved jade face, flat black and slender, encircling its own depth and dangling two inches below my breasts. I understood little except that time taken to craft this piece was the mark that measured a man. No macho milieu for Miguel.

As my retreat to Catorce flew by, I merely caressed Miguel’s work, but he described it infinitely: how long, how much time, how many nights by firelight. I had hardly a clue as to the geo-graphics of where each bit of stone or metal originated. But I breathed the freshness of the yielding soil. And I coveted the particular priceless spreads of time spent crafting each piece. In short, I was saturated with Miguel”s satisfaction in his work. I visited and returned to Miguel’s corner.

On the second day, I gave him my watch to replace its worn leather with a sturdy silver band. Confidently and casually he left me with all his wares, returning later with tools and silver wire to complete the task. I watched his fingers work the wire, his head bent low revealing one white wedge in the baseball cap worn backwards to warm the wind.

His long dark hair hung in a ponytail, a nicked jacket covering a more tattered sweater beneath. He squatted on the wide stone sidewalk, one sandaled foot before the other, raw laced beige leather protection on which he balanced perfectly.

On my third and final night in Catorce, Miguel slipped easily into the inn’s restaurant where I sat by the fire. I sensed that his matted hair, body odor and old, layered clothes might be unwelcome at some tables. I motioned him to mine.

While I ordered another coffee and dessert he continuously fingered something inside a left jacket pocket where he also warmed a gloved hand. Finally he withdrew an eagle taking form on an oval black stone.

I looked into dark liquid eyes set under bushy brows. His eyes struck my soul as I struggled to piece words together, words which would not come. I confronted desire and guilt. I was determined to possess this most precious of pieces, though I was short of cash. I signaled Miguel with “manana,” one of the only Spanish words I knew, while pointing to the plaza. I desperately wanted to be in his presence one more time.

Finality sunk in unbidden. Speaking of “manana” had veiled his pock-marked face. His eyes froze with disappointment in me which I could not ignore. “Manana,” he motioned repeatedly for my edification, might never come. All that is given is today.

On Sunday morning, I packed my car and turned tentatively to the plaza. Miguel was there, and I walked in his direction.