God’s Waiting Room

By Mikel Miller

One of the most interesting people I’ve ever known at Lake Chapala had a remarkable philosophical perspective about aging.

One of the most interesting people I’ve ever known at Lake Chapala had a remarkable philosophical perspective about aging.

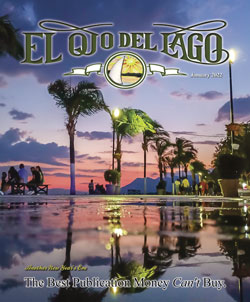

“Ajijic is God’s waiting room,” he told me one day during lunch on the plaza three years ago, gesturing at groups gathered under umbrellas in the early afternoon sun. I laughed as always when enjoying his insights about life, especially his views on how aging improves both people and wine to a point.

Many local residents remember when retired psychiatrist Roberto Moulun arrived in Ajijic in 1999, and how he attracted friends early on with his charm and quick wit. Some are fellow writers who appreciated his pursuit of perfection; two others are friends who sought his compassion in coping with personal issues, including the loss of loved ones. “You have no idea how much he helped me,” one told me. “I don’t think I would have recovered without him,” said the other.

He was a gifted story-teller, and a helluva writer too. He won three annual best fiction awards from El Ojo del Lago for short stories. However, his opinions about the writing of others attracted few close friends in the Lakeside writer community. After listening to a poet read about cicadas one day, I watched in amusement as Roberto signaled for the microphone and then growled his criticism: “That’s the most words I’ve ever heard about nothing. My advice is to burn it.”

Some of us also knew him as much more than just an aging expat hobbling to writer meetings using a four-legged walker, and becoming dependent on friends for rides. I visited him often in his humble home in West Ajijic, looked through his scrapbooks, and marveled at the breadth and depth of his conversations about classic literature, fine art, and music. We shared simple meals together with his live-in caregiver and her two children. And I watched him share stories with her five-year-old son who, in return, gave an elderly man new purpose in his last years.

He claimed ancestral nobility from Spain, a scion of parents who owned a large coffee plantation in Guatemala. Blessed with a brilliant and curious mind, he graduated college at fifteen and from medical school at eighteen. He always had compassion for suffering in life, human or animal, and led a protest in medical school against using healthy animals in laboratory experiments. After his internship at the Menninger Foundation in the United States, he dedicated his medical career in Hawaii to helping people with psychiatric problems. On a larger scale, he assisted International Red Cross disaster teams as a grief counselor.

Planning to retire in the early 1990s, he returned to his homeland but leaders of warring guerilla and government forces warned him against staying. Instead, he returned to Hawaii and wrote The Iguana Speaks My Name, a nuanced novella using magical realism to portray Guatemalan villagers coping with the thirty-year civil war that resulted in the genocide of 200,000 indigenous people. After closing his medical practice, he moved to Ajijic.

Sixteen years after he wrote the novella, it was published in a combined volume with ten short stories from Guatemala. Kirkus Reviews named the book one of the top twenty-five independent books of fiction for 2012, and it won second prize in a national competition in New York City in 2013 as the best first book of fiction. The award-winning book is available on Amazon.com.

He continued to write while he was waiting, although his eyesight deteriorated as he neared ninety and he could no longer use a computer. Over his mid-morning coffee at his favorite table in the plaza, “corrected” with Tequila, he would scribble lines on napkins and test them on friends who happened by. The scribbling was almost illegible to me when I tried to read it, so he would speak them to me with reverence. Friends said he tested the same lines with them, too.

Two years ago this summer, he was diagnosed with inoperable cancer and accepted it with medical stoicism and religious faith. In his final days, I went to check on him at his home, where he was frail and tired as I sat at his bedside.

“Six angels came to visit me last night, and we talked and talked for hours about what it’s like in Heaven,” he said. He lay back on his pillow and waved his bony arms in the air to show me where they stood. “I know you don’t believe me, but it’s true.”

Sitting at the plaza in Ajijic’s “waiting room” for many years helped him accept aging, and allowed him to keep writing. And I believe that talking with angels at his bedside one night helped him to begin a new chapter.