A Mennonite Madeleine

By Harriet Hart

When I learned that our itinerary of Mexico’s Copper Canyon included visiting a Mennonite colony, I was apathetic; unenthusiastic, I couldn’t have cared less. I grew up among Mennonites in Southern Manitoba which has communities with names like Plum Coulee, Rosenort, Grunthal and Steinbach, all populated by the followers of Menno Simons.

When I learned that our itinerary of Mexico’s Copper Canyon included visiting a Mennonite colony, I was apathetic; unenthusiastic, I couldn’t have cared less. I grew up among Mennonites in Southern Manitoba which has communities with names like Plum Coulee, Rosenort, Grunthal and Steinbach, all populated by the followers of Menno Simons.

When I attended Silver Plains School, a one-room schoolhouse that had once been a church, the student body consisted of five Holdeman Mennonites (very conservative), three Métis (the result of French and aboriginal pairings) and two WASPS. I was in the minority.

In grade one I shared a two-seater wooden desk with Lorraine Rempel who was slightly slow intellectually and wore shapeless home-made cotton dresses, but sported a set of blonde braids so thick and intriguing that my six- year- old self was overcome by temptation. One recess I let down Lorraine’s hair just so I could see what it looked like. Mrs. Rempel, her own braids coiled beneath a black skull cap, descended on our school the next day and to my astonishment, it was Miss Murray, our teacher, who was in trouble while I went unpunished.

My contact with Mennonites went beyond elementary school. In Morris Collegiate my first love was Kenny Kehler, whose poor overworked mother had eight children. The Kehlers attended one of the seven churches the town boasted; at least three of them were Mennonite sects. As social convener of Morris Collegiate, I was told that the school graduation dance had to be held off- site in the Legion Hall, so the Mennonite parents would not be offended. Our high school principal, Peter Dyck, convinced the school board that he couldn’t find a French teacher (despite the close proximity of the Francophone villages of Ste. Jean Baptise, Ste. Pierre and Ste. Agathe), forcing us all to study German as our second language.

Our modest home library was filled with titles like Forever Amber and Brief Gaudy Hour but surprisingly included a hard cover edition of a history of the Mennonites titled In Search of Utopia which my father read so he could understand our nearest neighbors better.My mother’s kitchen shelf had a copy of the Mennonite Treasury of Recipes with cookies called Dattelkuchen and Berliner Pfaster. It is one of the few mementos of her I still possess.

Steinbach is a prosperous Manitoba town known for its car dealerships: Penner Dodge and J.R. Friesen & Sons Ford were the pioneers when it came to car sales. My Grandpa bought one of the first cars ever sold by the Dodge dealership back in 1927; 25 years later I rode with him in a parade celebrating their success and honoring their early patrons. This seems ironic since the traditional Mennonites, like their Amish cousins, eschew motorized vehicles and travel by horse and buggy. By the time I got my driver’s license, Steinbach had earned the nick-name car city; even local Winnipeggers drove out to purchase their cars from the town’s honest, hard-working and prosperous merchants.

And now, here I was in northern Mexico, riding a tour bus approaching the small city of Cuauhtémoc. When I heard Martin, our guide saying: “Here’s the best place to buy an SUV or a pick-up truck,” I paid attention. The wide highway leading into town was lined with car dealerships and businesses selling farm implements, John Deere Tractors and combines. How peculiar yet familiar, I thought. Businesses had names like Manitoba Ventanas y Puertas.

Where am I? I wondered. Is this a bad dream?

We stopped at the Museo y Centro Cultural Menonita.

“My name is Tony and I come from Altona, Manitoba” a fresh faced, virginal young man said by way of introduction.

“My name is Harriet and I come from Morris (30 miles away),” I piped up. Tony was thrilled to meet someone from so close to his birthplace.

“This colony is called Manitoba,” Tony continued, “because the original 5,000 settlers came from there back in 1922.” He explained why those Mennonites left Canada and settled over 2,000 miles to the south. The government had passed legislation forcing Mennonite children to attend public school which the elders feared would corrupt them. Their schools taught the Bible in German and little else.

The original 5000 immigrants to Mexico obeyed the Biblical injunction to go forth and multiply and without intermarrying with their Mexican neighbors swelled their numbers to over 50,000 in just 8 decades. The colony’s museum held familiar objects: a wood stove and cream separator, iron bedsteads and tin canisters. Marcel Proust bit into a Madeleine cookie and wrote In Remembrance of Things Past and here I stood in the museum’s gift shop, eating a ginger cookie and experiencing a flood of memories flowing as fast as the Red River in spring.

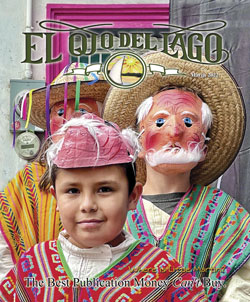

The Manitoba Mennonite colony in the state of Chihuahua is like Steinbach South with its wide streets, its ostentatious homes, its flower beds and John Deere tractors. A woman in a shapeless cotton dress was planting red geraniums in a wooden wheelbarrow outside the museum as we left. Blond men in denim overalls carrying black tin lunch buckets were leaving the cheese factory as their shift ended.

My fellow travelers were asking Tony what Mennonites believe.

“It’s pretty straightforward. We believe in adult baptism, and we don’t believe in going to war,” explained Tony.

“Why are there so many different churches?”

“Some of us are more liberal than others. It’s more about how to live than what to believe. Here in Chihuahua we can drive cars, dress in modern clothes. The really traditional folks have moved away…some into South America.”

I had recently read Irma Voth by Steinbach native Miriam Toews, a novel about a young Mexican Mennonite whose patriarchal father drove her out the door, down the road and onto the nearest bus to Mexico City and freedom. I had many questions myself like: What goes on behind these fancy doors? How are women treated? Why are Manitoba Mennonites much more assimilated into mainstream culture than Mexican ones? Were the elders right—does integration into the public educational system blur cultural and religious differences?

But most of all, I wonder whatever happened to Lorraine Rempel Did she escape like the heroine in Irma Voth, or did she spend her life sewing and mending, baking ginger cookies, planting geraniums and bearing children? I hope she got to let her hair down one more time, but somehow I doubt it.